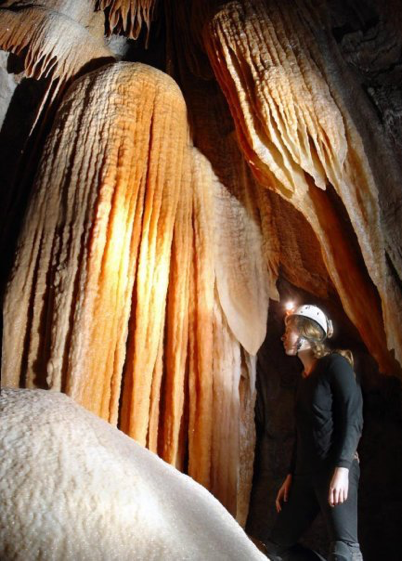

005: Deborah Johnston explores Mammoth Cave, NSW

Deborah has been exploring and documenting caves all around Australia and New Zealand with the Sydney University Speleological Society (SUSS) for 15yrs. She is passionate about finding, documenting and sharing new cave discoveries - both above and below water.

Her passion for cave exploration was recognised by leading Australian divers who mentored her so she could continue her research underwater by sump diving; where getting equipment to the dives within the caves often involves hours of backbreaking caving, climbing, crawling, squeezing and abseiling through mud with heavy bags of dive gear just to reach the waters edge.

Deborah's main cave diving interest has been at the famous and ancient Jenolan Caves (the worlds oldest dated cave system) which is home to a long history of incredible diving feats spanning from the 1950s to present day. It is here Deborah and her team of 'SUSS' divers have made many significant discoveries by working together on monthly exploration trips.

Sump dives are harsh, deep and technical, little-to-no visibility, with sharp and unstable rock, and tight restrictions; all requiring creative gear configurations and meticulous planning to succeed.

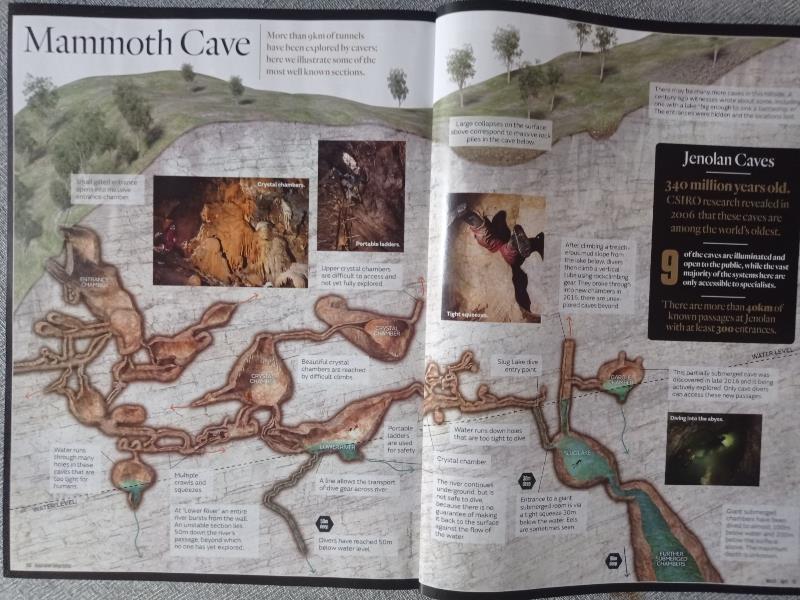

Below are some tips, pic and videos to help you when listening to Deborah's explanation of Mammoth Cave (click map to enlarge)

Deborah talks about three different exploration dives in Mammoth Cave at Jenolan Caves - NSW Blue Mountains Australia

Ice Pick Lake

About an hour technical dry caving to reach the lake - hardest access of the three with challenging climbs and extremely tight vertical squeezes. An absolute ball busting slog!

This dive is fairly short and shallow but very exciting because it heads off the map into a true unknown. It's currently ending underwater in a tight vertical rift buried in suspended silt that no one has been able to pass.

I explored this with Alex Boulton and Adam Hooper (who have since retired from cave diving which is a great loss), Greg Ryan, and Andreas Klocker who flew to Sydney a few times specifically to help me with this. There are two airbells and one has a 20+ metre dry rift climb above it. I'm too clumsy and chicken to do these climbs myself on the wrong side of the dive. I need help to continue here (if you know anyone!!). The furthest point I reached had a loud echo coming back when I yelled, indicate a lot of cave just out of reach...

https://vimeo.com/106373682

Lower River

About 45min dry caving to reach. This is (as far as I know) the deepest no-mount dive in the world (55m). It steps down in a series of tight vertical shafts meaning you enter it feet first with tanks detached. Going down is easy because you just slow the drop with a leg spread against the walls. Going back up is more like rock climbing underwater. You can't do this in a drysuit which makes for a brutally cold deco in the high flow. Total misery material.

It's exciting exploration because there is over 2km of limestone and huge dry caves between where the river comes out in the cave (a tire sized hole in the wall) and where it sinks on the valley surface. There is no other connection point to the river, meaning upstream exploration is likely to pop up into previously unvisited dry caves.

On my last dive there I found a cave crystal in the rubble which can only have fallen in from a dry passage upstream - proving some is there.

The exploration stalled at near 50m where a steep sandbank in a tight tunnel is unstable and collapsing once a person blocked the water flow (forcing the diver into the ceiling in a sort of reverse buried alive scenario). Rod Obrien and I did this exploration but I wasn't strong enough to manage the vertical no-mount climbs when we had to move from 7L to 12L steel cylinders at depth, and he (a big lumberjack build type) was far too large to stop the sandbank collapsing once blocking the flow in that small space. We needed a smaller stronger restriction experienced diver who could also do high altitude deco diving - and that just didn't exist.

There has been extreme flooding since then, so that sandbank might not even exist anymore?! It definitely deserves another look, it's just really hard work.

It is the most promising diving lead in Australia in my opinion - and the only Jenolan dive with clear vis!

https://vimeo.com/86284449

At Mammoth Cave’s Lower River, Dean Coleman (left) of the Sydney University Speleological Society helps diver Deborah Johnston prepare for underwater exploration. Image credit: Alan Pryke

At Mammoth Cave’s Lower River, Dean Coleman (left) of the Sydney University Speleological Society helps diver Deborah Johnston prepare for underwater exploration. Image credit: Alan Pryke

Slug Lake

This is the deepest cave dive in Australia which is why it gets the most interest (and the only funding!). The legendary Ron Allum dived to -96m here in 1998 and could see the massive passage continuing downwards as far as his huge torch would shine. That was a big bore tunnel continuing down on a steep slope where - when following the roof - he couldn't see the floor below or walls either side. There is nothing else like that at Jenolan because these passages were formed in a different way to the rest of the known cave.

We've been campaigning for years to be allowed rebreather diving here which has not been successful. Rebreathers are currently illegal in this area.

It's about 1.5hours dry caving and a real slog, especially with OC gear. The water starts at about 900m above sea level and is 14degrees which complicates our deco obligations, and most dives are rather physical lugging gear back and forth.

Near the start of the dive is a tight flattener (about 30m deep) which needs to be dug out periodically. It's bedrock top and bottom when dug free which is low and wide. You have to turn your head to the side to fit a helmet through which can be unnerving. It's definitely not the sort of place you'd want to have any gear issues (as I found out the hard way one time!). It then opens up into a massive chamber with too much suspended sediment to ever see properly.

The dive then continues down underwater into the unknown, or up to a large airbell. We started this exploration at the airbell hoping to find a dry entrance in from the mountain side above, or a dry cave passage bypassing the underwater squeeze. We bolt climbed here over many a long trip and found quite a lot of beautiful dry cave passage which was tricky to explore with lots of abseils and climbs between passages.

We didn't find any connections to the surface or exit side of the cave, but we did find a whole separate lake which is still unexplored despite one dive (due to the sheer logistics and physical effort of getting the equipment there). The one dive managed so far was bombed out immediately by an explosion of mud coming off the diver as he entered. It's still a big question mark waiting to be solved.

The way this dive passage formed is fairly unique and means it has the very real potential to be staggeringly deep. It's likely to be too deep for humans, but also seems to exceed the technical field capabilities of current ROVs. It's super exciting and promising exploration that has been limited by a lack of divers with the mix of skills required to tackle it.

Deborah and her team rely on experienced volunteer dry cavers such as David Reuda (above, behind) to help them safely navigate these passages. Image: Alan Pryke

Deborah and her team rely on experienced volunteer dry cavers such as David Reuda (above, behind) to help them safely navigate these passages. Image: Alan Pryke